Societies need to be steered towards sustainable ways of living, because our current way of consumption, energy use, coliving with nature and each other is not viable – there is no debate on that. The debate lies very much in the way of achieving this: the transition approach argues that we need to let go of our traditional structures and give room for new forms of governance. Transition management aims to facilitate this process, envisioning an important role for the local government bodies. We explore this topic and search for the right questions with Derk Loorbach, director of DRIFT for transition organisation.

“Transition management is a range of new instruments, strategies and actions to influence the speed and development of sustainability transitions.” – we can find this in one of the articles on the DRIFT webpage. In what aspect do we talk about sustainability here?

Derk: The starting point for transition research is that the existing systems we have now are unsustainable and the way policy makers try to improve them in the name of sustainability do not make any difference. Improvements in the existing systems – energy systems, mobility, food, education, healthcare system – don’t change their core, unsustainable nature. From a transition point of view, it is this way of working that is unsustainable, thus transition management is a strategy to challenge policy logic and try to identify what kind of alternatives, niches can emerge and become building blocks for a better future. In other words: transition is a systematic shift out of equilibrium towards a new future – first in a disruptive, chaotic way; which can be smoothed by transition management.

So transition management helps governance bodies to embrace the unknown, the approach of not being in control.

Yes, that’s the paradox in governance transition management! Policy making is about control, power and planning – and that doesn’t work in transition. On one hand, we know from climate, biodiversity and social justice points of view that we need a radical change in our system to make it sustainable, otherwise we get extreme climate change, social inequalities, biodiversity loss and all sorts of major issues. On the other hand, we need to achieve the changes with policy, but the policy logic itself is not fit for the problem. Instead of improving the existing systems, we have to invent together the changes that our systems need and that’s completely opposite of what planning does.

So how does the transition process work?

Let’s take the example of the transition towards sustainability in the context of urban mobility: the status quo is that the system built on cars is not sustainable. Policy makers try to make all sorts of policies to manage traffic jams, parking problems and air pollution, but they keep investing in a car-based system. The radical alternative would be to design cities for people by cycling, shared and free mobility and get rid of cars as much as possible because they take up space and it’s a waste of resources. Alternative options are created on a niche level by whom we call social innovators: people who already changed their behaviour. They might be bike activists, social entrepreneurs who came up with car-sharing schemes; ICT nerds that came up with apps or bigger companies that come up with Uber. This is the phase of transition when the old system is more and more debated and the alternatives are there on a small scale, but people still don’t see how they would work on a bigger scale. This co-living of solutions creates chaos, uncertainty, it is a very uncomfortable process to go through. Policy makers want to go back to stability, also there are a lot of people who have something to lose in this process: companies, investors or just people who can lose their careers or just people who like their cars. So if we tell them that we need to move to a system where nobody has their own cars anymore, they can’t imagine that and become angry. We do know the new alternatives are technologically possible and from a sustainability point of view are needed, so if we do it in the right way it is the right thing to do for society and ecology. But people just can’t imagine that could happen. In order to make these changes happen, political leadership is also needed: in some cities, the mayors and decision-makers decide that they empower those niches and are ready to make more fundamental changes, so it gets supported by the system. This is the process transition management aims at facilitating for all actors, especially for policy makers.

What are the tools in transition management to facilitate this process?

If you take the transition management approach as a starting point, that has implications for strategy, governance and policy. The key is that you need to focus on the transition you want to achieve and look outside of the existing context to map the current societal dynamics: investigate what is happening, where are the emerging alternatives and how they interact. The approach you need to take is backcasting: from the transition you want to achieve think backwards: where are we now, and what kind of change we need from the status quo to achieve it. That is for the long term; in the short term, one should work with transition experiments, in the social entrepreneur’s logic. You have a long term direction and a strategy, identified with the help of backcasting, and you start somewhere with experimentations, learn from that and readjust your direction. This kind of logic is the instrument for transition management.

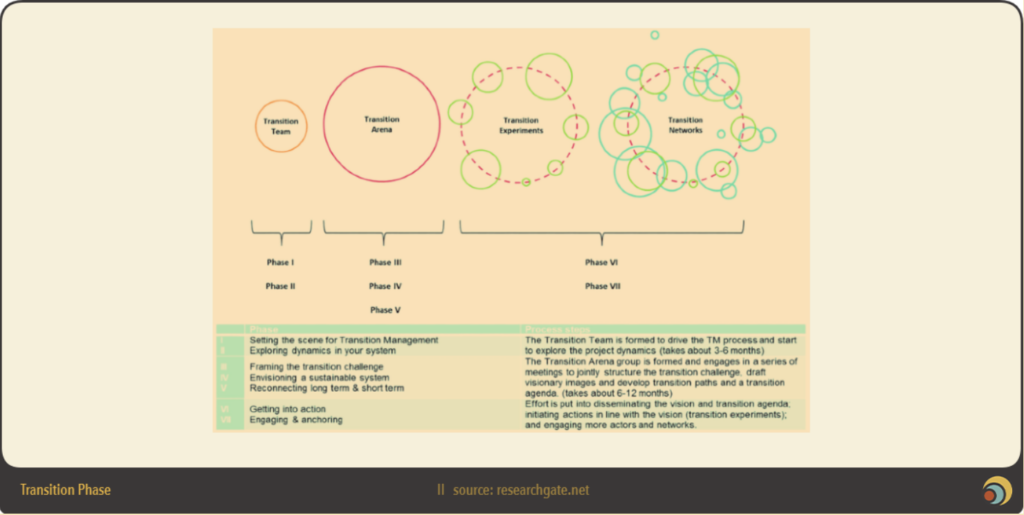

Once we are in the transition management logic, we use the transition arena approach to influence the discourse in a specific domain. Basically the idea is that we identify changemakers within the existing system but also at the niche level, and we bring them together. It is a relatively small scale process with 20-25 people, with them we go through a sequence of 5-6 meetings, where we develop a transition narrative as a roadmap to achieve the desired changes.

To further explore the tools, I recommend the Workbook for Urban Transition Makers we did for the currently running TOMORROW Horizon 2020 EU project. It is an urban transition management manual, with the description of the tools we identified.

Basically social innovations are transition experiments, so we can say that it is happening everywhere at different moments.

Transition experiments are different from social innovations: again rooted in the difference between the logic of planning and backcasting. In innovation projects, you have the solution for an identified problem and you want to test it, evaluate and go with it or leave it behind. A transition experiment is embedded in the bigger narrative, it is much more an experiment than a tailor-made solution. The transition experiments formulate the steps towards your desired transition, which also helps to formulate the learning question you want to explore and research. The ideas for the transition experiments come from the transition arena work with identified change makers. So it builds on initiatives that are already there, and use them for learning by doing. In this logic, you distance yourself from the thinking in problems and solutions logic.

So your job as a transition manager is to find the marginal initiatives and empower them to become mainstream.

Yes, that is part of the story in what we call transition management 1.0, the early phase. This phase is all about empowerment, creating a counter-narrative, empowering and connecting the niches. If you move on, more and more people see that the change is needed, but maybe they cannot change it from the existing structures, so the system is still stable, here the transition management is all about bringing together the growing niche movement with the policy makers and the people from the regime that is open to change – this is transition management 2.0.

This is where we are in Rotterdam, where the policy makers are really engaged; in the Netherlands in many different sectors, there is no discussion anymore about the need for transition. The complication is that power dynamics change in the actual transition phase, the regime partly collapses. In many domains, the powerful actors are transition-washing by adopting the words of this approach but bringing the transition under their control. For example, we shift towards renewable energy, but we see large wind farms with a lot of public subsidies given to big corporations; which keep the old structures in place, just with new instruments. At the same time, there is the niche movement of energy justice and commons-based energy systems, much more cooperative and democratic. The real transition is to design a new sustainable and just energy system, not to be based on centralised, liberalised, profit-making energy systems. In this phase, transition management is about making sure the institutional changes are happening.

So in transition management 2.0, the real transition, the transition management’s job is to make sure the changes are not only transition-washed, but they imply real transition scenarios.

It is about detecting the principles of the niche and keeping them in focus. The challenge is that if we want the whole system to change, we cannot depend only on the initiatives that started the transition. For example, energy cooperatives are great, but that’s not the way we can provide energy to the whole country or the whole world. So the principle of the niche should be institutionalised, this is where the government needs to step in by facilitating the market and creating the institutional context.

For that you need to have the government on board.

The interesting thing is further you come along, the more civil servants get engaged in the change. The government itself is a very ambiguous thing because they are part of the problem, but they are also a necessary part of the solution. Ultimately society depends on having agreements: which is the government. Municipalities and local level, in general, play an important role in the transition, because the national level is often entangled with the system of production. We even prefer referring to the trans-local level, because we have global platforms to share information, so you can learn from global examples and at the same time you have to make it locally rooted to find the local solution. The role of this network of cities, digital platforms and research help to diffuse the ideas. Policy at the local level can really help to accelerate this transition, ultimately also help change policy itself.

And the change can be transferred to the national level once, right?

Yes, but the unfortunate lesson from history is that the national levels will probably only be transformed through disruption. It is very rare historically to find enlightened politicians at the national level that say: we really need to let go of our current positions and embrace this uncertainty and the transition. Leaders of some countries like New Zealand and the Scandinavian countries go in that direction: young women mostly, who have the guts. The rest of us are still ruled by white men tied to the post.

You outlined different phases of transition; could you tell us concrete examples from the projects you carried out for each level?

We collaborated in a series of projects with the city of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, in order to facilitate the sustainable transition in the domain of mobility.

The work started in 2015: we created a transition team with 3 civil servants and 2 transition researchers, and carried out a transition analysis on the mobility system of the city. As a result of this analysis, we created a transition arena with 20 change makers linked to mobility and 50 civil servants. We worked together for 6 months and created a new discourse on mobility: we identified the strategic axes of social mobility, inclusion, public health and access to the city. Before that, the discourse was centred around facilitating mobility from a technical approach.

In the upcoming years, the cooperation with the city of Rotterdam continued: we upscaled the use of transition arena, and organised a mobility table involving 150 actors, niche and regime actors to start a dialogue based on a shared ambition: stating we need to move towards 0 emission social mobility system by 2030. That was the very radical starting point, starting from which we developed a mobility transition agenda. Many civil servants were involved and the climate agreement was backed by 2 edelman of the city, so it had the political support needed as well. It was an informal process with formal support: they didn’t guarantee the implementation, but through the process, new connections were made. Since then a number of breakthrough actions from the agenda were implemented, they changed the structure of the city. For example, 4000 parking spaces were removed, they closed off a number of car lanes, increased the number of cycle lanes, issued new regulations for shared mobility parking facilities, pushing companies towards change. That is an example of transition 2.0, a real move with engaged governance structures on board; the learnings from this process are published in the Journal of Urban Mobility.

Are there any examples of cities already in transition phase transition 3.0?

Transition 3.0 is really far away in the Netherlands, we haven’t seen successful cases of sustainability transition yet, in the next 10-15 years we are anticipating huge systemic shifts. Internationally we can see some good examples: Copenhagen, Oslo and Paris are already in the 3.0 phase for me. There the transition agenda is the dominant policy already, every intervention they make in the city is based on a different kind of idea, transitioning towards a more sustainable and just functioning.

Derk Loorbach is one of the founders of the transition management approach as a new form of #governance for #sustainable development. He has over one hundred publications in this area and has been involved as an action researcher in numerous transition processes with government, business, civil society and science. He is a frequently invited keynote speaker in and outside Europe.

He is the director of DRIFT for transition organisation and Professor of Socio-economic Transitions at the Faculty of Social Science, both at Erasmus University Rotterdam.