… How a UIA project in Szeged paves the way to new forms of going to work

Every morning, billions of people around the world wake up, have breakfast, dress up and leave to work. But how do you commute to your workplace? As transport is one of the greatest sources of CO2 pollution, people should be motivated en masse to choose sustainable modes of commuting – such as walking, cycling and other micromobility solutions and public transport – over car use. But how can this be done? And, crucially, how should companies be involved in getting their own workers out of their cars?

SaSMob, a UIA project at the City of Szeged, in south-eastern Hungary, looked at exactly that. Therefore, we talked to Antal Gertheis, managing director of Mobilissimus, a mobility planning company involved in SaSMob as a project partner.

Workplace mobility, to put simply, is about how workers commute to their work. This sounds simple enough, but of course as many of us experience it daily, a lot of workers commuting at the same time can cause a significant headache for transport planning, and is the main driver of problems such as traffic jams and overcrowded transit. On a more abstract level, changing the commuting habits of workers by encouraging them to choose greener and more sustainable is key to the transition to a greener economy and therefore a key aspect of tackling climate change. Therefore, sustainable transport (public transport, cycling, and micromobility) should be turned into a competitive and preferably better alternative to unsustainable car use.

Transport projects, good or bad, tend to be big, whether they are new railway or tram lines (or tramtrain, a mode of transit that is being introduced in Hungary for the first time between Szeged and Hódmezővásárhely). But just as importantly, smaller interventions or awareness campaigns might be highly effective in making sustainable transport more competitive. Building a couple of metres of pavement to connect the factory to the nearest bus stop, relocating bus stops, connecting factories to the city’s cycling infrastructure might not be the fanciest thing to do, but can significantly improve sustainable transport options.

The importance of this goes beyond how we commute to work. Workplace mobility also has a knock-on effect on people’s transport habits more generally. As Gertheis explains, if someone commutes to work by public transport, then they are likely to have monthly or yearly passes to use transit. And vice versa, those who use other modes of transport to commute, will not have passes. This, in turn, affects the transport choices of individuals more generally: those who have already paid for public transport, will be more likely to use transit on weekends, while those who don’t have passes might use their cars when travelling on weekends, even if there are competitive transit alternatives.

SaSMob has two legs. The first focuses on major employers: they surveyed how employees commute to their workplace, created mobility plans and implemented interventions, such as small-scale infrastructure projects, the creation of new services, or awareness campaigns. The second leg focused on the creation of new technologies by the computer science department of the University of Szeged. This focused on creating new sensors, smart city technology, and a data centre, that were cost-efficient and would make Szeged transport more efficient at the city level.

As the project is coming to an end, we can take a look at the list of case studies that were published in their case study guide, to see just how complex this project was. (The guide is available here, so far only in Hungarian. An English version is expected later.)

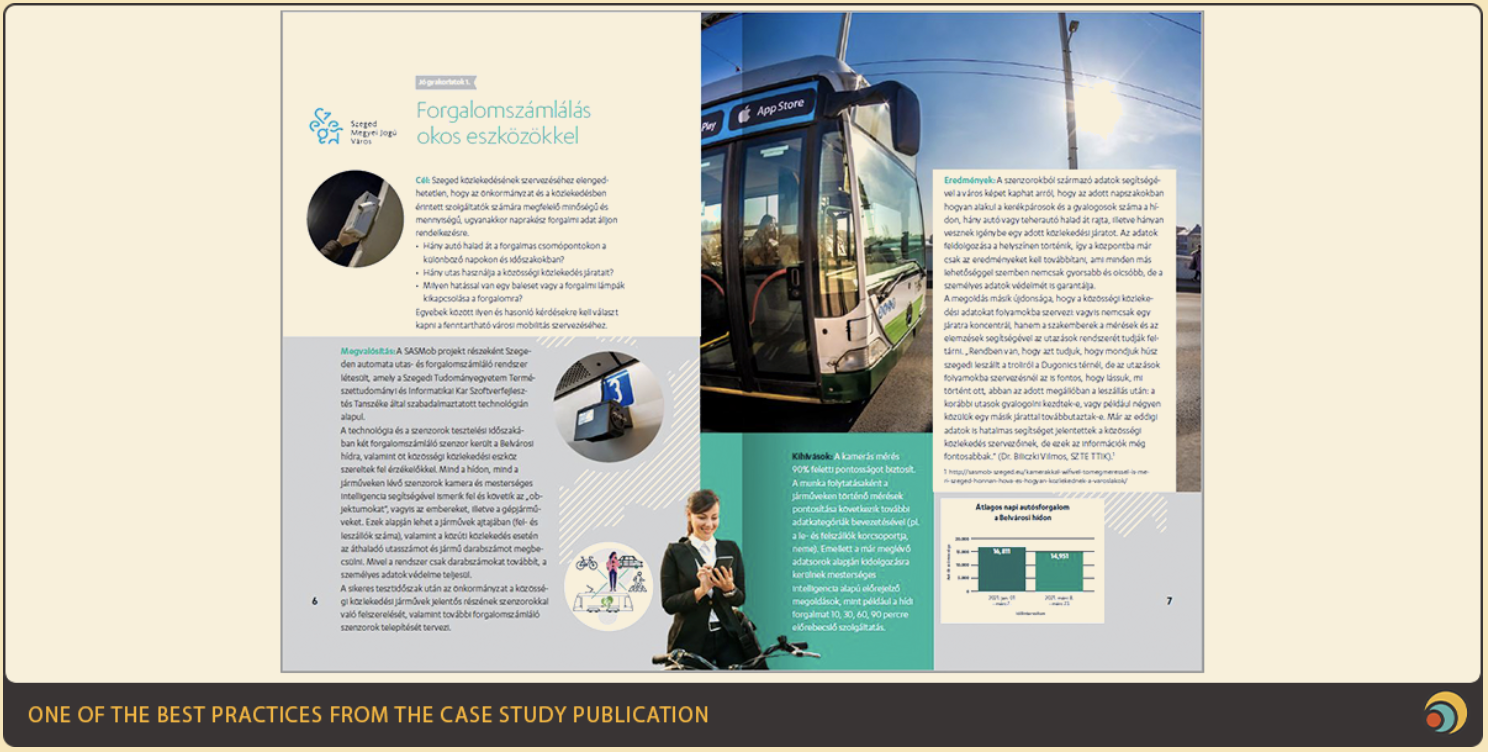

- Measuring mobility with smart devices

- Smart city data centre

- Expanding bike storage capacities at workplaces

- Company schemes for bicycle and electric scooter lending

- Creating bicycle service stations

- Campaign to popularise cycling

- Children’s drawing competition: transit of the present and future in Szeged

- Ticket vending machines at workplaces

- Public transport maps at two company sites

- Sustainable mobility management university course

- Survey on the workplace impact of the COVID19-pandemic

- Resetting traffic light to support public transport

In order to understand workplace mobility, we need to first understand the differences between different workplaces. SaSMob involved a wide range of local companies – including IT companies, the university hospital, a meat industry company (known for the Pick salami) as well as the municipality itself – and have found that there were significant differences between office-based and factory jobs. For a start, offices and factories might be located in different areas, with centrally located office buildings being more appropriate for public transportation, cycling and walking already. Second, the project found that factory workers were more likely to commute from longer distances, while office workers are more likely to live closer to home. This again means factory workers are more likely to drive to work, Gertheis explained to me.

Of course, when talking about workplace mobility, there is no way to avoid the elephant in the room: the pandemic, which has impacted both the ways we work, and the ways we commute. We might sometimes forget, but not everyone was able to work from home. This means that as public transport usage declined, with no alternatives available to longer journeys, car usage became more prevalent. It also means that now more than ever, cities should promote sustainable transport.

How should this be achieved? Not all of the Szeged experience can be directly scaled up for other cities. For example, smaller towns may have significantly less developed transit systems that they might need to work on, but conversely may not need advanced sensors and data processing technologies with only a few traffic lights in their towns. In larger cities (in Hungary, most notably, Budapest) mores emphasis should be put on public transport, and smart city solutions can and have to be connected to already existing systems.

However, the main learnings of SaSMob can be adopted regardless of the size of your city or town. The most important is that in order to tackle the problems of workplace mobility, you need close cooperation between local employers and the municipality. First, employers have the relevant information that can make sustainable commuting a competitive alternative to car use. Second, conversely, employers would not normally see workplace commuting as their business, and therefore need the municipality’s active role to start working on transport interventions. And third, many of the SaSMob interventions required that sustainable transport goes to the factory door and even inside. Such measures, such as allowing workers to purchase tickets inside their workplace or setting up info screens with real-time public transport information, also required the municipality and municipal companies to work with employers.

For this, you need high-level political support for any such project to be truly successful. While you can do transport projects half-heartedly, you cannot achieve the required integration between the municipality and local companies without mayoral commitment. Similarly, company managements also need to commit to making sustainable commuting more competitive.

This, we believe, is the greatest takeaway from SaSMob: if you want to make commuting more sustainable, you need to get all stakeholders to the table, and make them committed to cycling or public transport. And, given the urgency of the climate emergency, you better start this now.

This month Antal Gertheis was our guide to dig deeper into the topic of urban mobility.

As an economist, he presents an integrated approach to his work: examine individual projects not only from a transport professional point of view but also from urban development, economic and financial point of view. He uses his experience in several areas of mobility planning: he is involved in the preparation of sustainable urban mobility plans (SUMPs), strategies, international research and collaboration projects, as well as feasibility studies and cost-benefit analyzes – including the #SASMob Urban Innovative Action project.